The America Phone

The airplane may have limits on your luggage, but U.S. border control should make you consider how much baggage you want to cart around on a mobile.

So, you're going to America. Bold choice. Travellers are steering clear of the U.S. these days in increasingly larger numbers. Maybe it's because so many are being arbitrarily detained, imprisoned and interrogated. United States citizens themselves aren't necessarily safe at the country's borders. Even babies are getting harassed by border agents and shipped out. Possibly it's because of more accounts about people disappearing while being held in American border control custody. Or it could be due to concerns about students or faculty on visas there being rounded up and deported for having been at the wrong place or posting the wrong thing on Facebook. The attacks on women should be putting us all off. There are also new threats for trans people traveling to the U.S. leading several countries to publish travel advisories. But you'll be fine, right?

But hold the phone... what's on your phone? Shared something snarky about that orange despot in the White House? Liked one too many dunks? Added a watermelon emoji to your Insta profile? Protest photos in your Google album? Attended the funeral of a high-ranking Hezbollah leader? The issues vary, all of them have caused someone trouble, but regardless of your right to remain, the new thin-skinned, easily offended approach to U.S. border control could get you seated on the next plane out, or in a detention centre for... some time. More people are having their mobiles inspected at U.S. points of entry, and getting denied entry for what's on there. Last month, a French scientist was denied entry to attend a conference for messages on his phone that criticised Trump regime policies related to his field. There have been other reports of it happening, but this one seemed to ignite a flurry of advice on how to prepare your smartphone for entering the U.S.

Some of the better guides

- Crossing the U.S. Border? Here’s How to Protect Yourself — by Nikita Mazurov and Matt Sledge, The Intercept

- Protecting Your Phone — and Your Privacy —at the US Border — Lauren Goode, Michael Calore, and Katie Drummond on Wired's Uncanny Valley

- Avoid Border Control Snooping Your Private Info by Using a Burner Phone for Travel — Palash Volvoikar, CNET (editorial note: yours truly takes issue with the misuse here of the term 'burner phone' but this guide has some otherwise useful information.)

The vulnerability of being in border control

Your rights are not the same as when you're walking down the street or in your house. Yes, the U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) can demand your phone for inspection (or any of your devices, really) without a warrant. And being a citizen won't stop the CPB from demanding access to your devices or possibly seizing them. Most guidance out there recommends to have your smartphone locked or preferably switched off during the border control process. No, doomscrolling in the queue. CPB could immediately inspect an unlocked mobile with no need for further permission. If it's switched off, what CPB can demand from you gets a bit weird thanks to the U.S. Constitution.

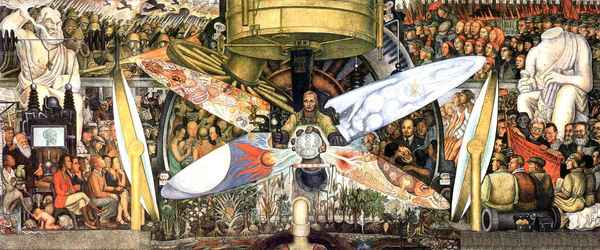

The Fifth Amendment protects people against self-incrimination, so no compulsory speech. You don't have to say anything that lets the law into your mobile. If your phone is locked with a numerical passcode, you get that choice. But if it's locked with biometrics — say, your fingerprint, or face recognition — then CPB can smash your thumb on it or aim the camera at you and get in. Because there's no compulsory speech involved. Dig? It seems the authors of the Bill of Rights (through which the Fifth Amendment was ratified with nine others) in 1791 weren't thinking about the eventuality of a do-everything screen that could be accessed with your face. Shortsighted, really.

You can refuse if you're using a passcode. But then CPB can decide to seize your devices and keep them kind of indefinitely. If you’re a citizen of the U.S. you can't legally be barred from entering for refusing this kind of search, though you could be held and interrogated for some time. But the law is a fluid thing in America, these days. U.S. The White House has suggested that some U.S. citizens have been deported by mistakes that it isn't in a rush to correct. Others have been detained for days and days. Children with citizenship have been deported without due process, because their parents had been targeted for deportation. So... no promises.

Things are getting far less certain for non-citizens, even if they have residency visas, own property, have jobs, etc. If you're a non-citizen, regardless of your legal status, refusing access to your devices at the border, CPB may decide to refuse entry on the spot. And again, this is all in the situation that laws are followed, which is not certain in the context we're now discussing. This regime is breaking laws as a way to invent new powers.

In the event you grant the nice border agent who may have the power to disappear you access to your mobile, they may just scroll through your socials quickly to check if you've said anything mean about president Trump. The other option the border agents have is to copy all the device data onto their own machines for more thorough analysis. That copied information is then saved for 15 years "in a database searchable by thousands of CBP employees without a warrant." All your photos, contacts, DMs, and so on. That's a long time. And does it get removed after 15 years? How would you really know?

Your phone away from your phone

So, you're still going to America. Welp, you only live once. And what you need for the trip is a YOLO phone. This isn't a "burner phone," that term gets misused a lot of the time. The goal of a burner phone is (very) temporary anonymity. Classically, a burner is a single-use phone. You'd get a cheap, prepaid mobile with cash, have your conversation, and then destroy the thing. It represents a single data point on the mobile network. Obtaining one, using it properly, and disposing of it comes with a whole set of operational security practices with the ultimate goal of anonymity and deniability. It's not just a device, it's a set of behaviours, many of them easy to screw up. It can be handy for crime, whistle blowing, source protection, and a few other narrow use cases. But I digress.

a YOLO phone is here for a good time, not a long time. It has low expectations. It's down for whatever is happening in Vegas to stay there. It doesn't necessarily need to be the latest, greatest model, it just needs to be up to scratch for the current tasks at hand. It's a mission-based phone, for a trip, a project or anything else that you may just want sequestered away from your usual daily carry device. And when you're done you wipe it. Back to factory settings. Dump it, gift it, or sell it.

I'm not going to go through a whole mobile security how-to in this post. There are three already listed higher, just scroll back up. And for good holistic digital security guides that include mobile phones, I've got you covered already, right here. YOLO phones are more about containment. If I were to score tickets for Keanu Reeves and Alex Winter's Broadway production of Waiting for Godot and needed to cross the Atlantic this September to JFK, I'd either want a mobile I haven't set up yet that I'd bought for cheap at the Lewisham CeX shop, possibly with minimal travel eSim functionality, or a phone I'm going to buy somewhere in Gotham, using yankee dollars I'll have already bought with what I bet will still be a stronger foreign currency. I'd want the contacts I'm going to put on it stored securely in an encrypted file I can safely get to later (and I'll want to have practiced beforehand that I can easily do it). Because what I don't want to do is travel through a U.S. border during these hostile times with a hard drive full of personal and work life.

That's it. The best mobile to go through a border with is not your mobile. And when you leave, wipe it and consider just leaving it before going back to the airport. Bring a book... like The Gulag Archipelago or something.

As important as the device — if not more so — is the communication plan. Who knows where and when you're going, what airports you go through and when and how they should expect to hear from you? What should they do if they don't? You don't really need a Hostile Environment level document (yet), but some people who go into areas of U.S. border control don't come out.

Have a good trip!