Beyond Provenance

This post is migrated from the old Wordpress blog. Some things may be broken.

I’m a slow blogger. Perhaps it’s one of the few aspects about this site to act as an indicator that the words here are in fact typed by human fingers. AI-powered sites are running conveyor belts of prose at a much faster clip. That aside, you’re just going to have to take my word for it. My clunky sentence structures, complex relationship with grammar and proclivity for typos and just bad spelling are all the human sign posts of a bespoke piece of artisanal web content. But there are no technical signatures to prove it. Nothing in this version of WordPress offers a watermark of authenticity. You’re going to have to trust me. Or don’t.

This post is about the importance of showing origin, human or otherwise, of media creations. Amid all the various emerging challenges and outright threats that generative AI poses (and there are a lot) the inability to prove attribution is a central feature across many of them. But it’s not as simple as just showing when something is generated by AI. The other disrupting factor is that it’s also now increasingly more important to be able to show when something is human-created I was recently reminded that I’ve been thinking of how to blog about this for some time. Another news outlet — an American outfit called Hoodline — was found this spring to have been publishing AI generated articles without attributing them as such. It’s not the first time a web publisher has tried this. It certainly won’t be the last.

The source of information matters. How we continue to prove that human beings are actually communicating to one another is becoming more fraught as it also gets increasingly vital to show. Generative AI is posing huge disruption to trust. The Reuters Institute at Oxford ran a survey across six countries that showed most people are less trusting of news that’s been produced with generative AI Tools, and by in large want it to be identified. Meanwhile, OpenAI has decided against implementing software it’s already developed that would watermark ChatGPT-created text over concerns that customers would then use it less often in their content. We want it both ways. The problem is not the technology, it’s us, we can’t be trusted.

The marketed promise of generative AI is to offer people the rewards for creation without the struggle of creating. Humans have an economising instinct that often prioritises the quick win: run the yellow light, eat the only slightly expired tin of beans. Software providers get this. It’s why whenever I log into Microsoft stuff to work, there’s the Copilot icon, asking if I want it to write my Outlook emails, draft my Teams message replies, revise a paragraph in Word, or design a page in PowerPoint. It’s why Adobe has AI that will turn your text into fully rendered illustrator files, or change your average photos into stunning works of postcard-looking Instagram wonder. Even as I write these lines in WordPress, there’s a little icon that shows up at every new paragraph asking if I want to have its AI expand or shorten my prose, or even change the tone of the whole thing.

At issue is provenance. Because we can’t just rely on people to consistently do the right thing, we need more of the technology to tell on itself, or rat out the technology that isn’t. A core piece of any ethically launched Generative AI should be to include traces of its own provenance. Likewise, the hardware and software people use to write, photograph, video, or create, needs to be able to show it. We have to show our work in more concrete ways, because we’re now producing it in an age where it’s easier to fake it, and accuse people of faking it. We are in an age when a byline isn’t enough. A copyright won’t do.

Let’s start with Carl Sagan: “Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.” It was a line he’d both written in a book and restated in his television show. It’s what became known as the Sagan Standard, and it’s not far from the pithy line by Christopher Hitchens, which says that “what can be asserted without evidence can also be dismissed without evidence.” That’s also known as Hitchens’ Razor. It is itself a riff on Occam’s Razor, dubiously attributed to a 14th-century English philosopher and theologian, William of Ockham. That one stated “entities must not be multiplied beyond necessity,” but has been modernised to into “the simplest explanation is usually the best one.” All three aim at establishing to what length people should go to establish whether something is factual.

Nearly any image can now be an extraordinary claim in the era of generative AI. “The simplest explanation” may not always be the most likely. That leaves a brutalist version of Hitchens’ Razor, in which media is more frequently doubted until it can prove itself. Generative AI is making it easier to churn out the fakes. The pretend people are starting to have hands with the correct number of fingers and smiles without a demonic set of teeth. The text can carry a more natural tone and read more human. As it gets easier to create more realistic augmented or entirely manufactured scenes, the key issue facing media creators’ credibility will not be the use of AI tools per se, but in how their work’s origin is demonstrated.

Proving authenticity is not a new fight. Fraud, forgery, plagiarism, manipulation of image and film and presenting it as authentic have been with us all along. As soon as there’s a new medium, someone figures out how to game it and systems are developed to deal with it… always after the fact.

Way back in 2006, not remotely analog times, the Reuters news agency was forced to issue a “Photo Kill” on two images taken by a freelancer during Israel’s war with Lebanon that had obvious signs of some Photoshop manipulation, spotted by a pair of conservative bloggers. I remember this because I followed it at the time. Even though these two photos were pulled, it became open season: was every other image also manipulated? Were the casualties being manufactured? A number of pro-Israel bloggers invoking “Hezbollywood” would go on to suggest that this was proof that claims of death tolls and damage shouldn’t be believed. Fast forward a decade and a half: far left bloggers and self-styled “anti imperialists” and “independent journalists” (using quote marks here for sarcasm and irony) would use similar tactics to discredit coverage of Assad regime atrocities by trying to discredit photos and video showing evidence of torture and the use of chemical weapons against civilians. In both cases, partisans seek to discredit any media running counter to their narrative, and will usually pounce on one or two bad apples to ruin the whole bunch. In conflict, the deluge of material is endless. It’s a numbers game. Eventually something’s going to be wrong. If you’re goal is propaganda and the generation of doubt, you just need to catch it and say this is an example of all of it.

Enter OSInt (open source intelligence), which was popularised by Bellingcat and others in the last 10 years or so, but its history is far older. In conflict coverage, it’s a team sport for armchair sleuths, and often a way of brute forcing proof or disproof of authenticity: Can you examine the shadows against where the location and time of day? Does the image’s sky match what the weather was on the day in that part of the world? Can you find the location on Google streetview to see if it looks the same? Does the shrapnel have any serial numbers that can be reverse searched? Stuff like that, and far more technical. There’s a lot more to it it’s a whole entire discipline, but for the purposes of this topic, we can leave it at this: OSINT can be one very manual way to brute force way to provenance. It’s other people showing the homework. It’s awesome, but it’s analog and painstakingly slow. it’s not meant to (or able to) prove or disprove everything.

All this was before the ubiquity of generative AI, which — while it was a fun toy when we were all hiding in hour homes from Covid-19 — continued to iterate into a massive disruptive force across everything, including media authenticity. More than early Photoshop manipulation or someone making a poor cropping choice on a picture, AI’s increasingly better ability to generate realistic false images and video and produce at least plausible text has propelled the need to show proof of origin.

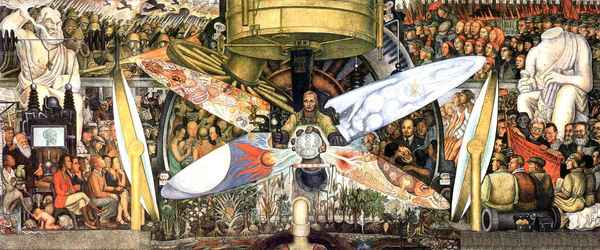

Provenance is the key problem for media workers to establish against the flood of generative AI material, or what Spider-verse films producer Christopher Miller called the “generic plagiarized average of other artists’ work.” We’re going to be talking about news and factual content in this post, but Miller’s point still works here. Run with it. Within this context it’s not about whether what the information provider is saying is true. People can lie, be inaccurate, mislead or misrepresent in completely analog and organic ways. It’s whether what they’ve created can be traced back to reality at all. Like an arms race in which the other side has a late start and poor odds of catching up, there’s an emerging parallel effort to create protocols and applications that show authorship.

What if the evidence of origin could be baked into the media? Technical proofiness has been cropping up in more spaces where journalists, digital rights activists and civil society types congregate. At last year’s RightsCon — Access Now’s annual shindig covering the intersection of human rights in the digital space — Witness, which supports activists who capture video and photographic evidence of human rights violations, ran a session that explored the opportunities and risks of emerging provenance technologies as well as new ways to more quickly detect synthetic material. In another session Witness focused on the other side of the same coin, how to ethically mark generative AI as such. Meanwhile, at this same event, there was also a presentation on Thomson Reuters’ collaboration with Canon to incorporate a suite of tools from the point of photo capture onwards to track authenticity, using a mix of cryptographic signatures, recorded metadata maintaining a record of editing history via blockchain. That’s right blockchain could find our what its special purpose is for at last.

All this is built on the open C2PA standard for proving authenticity. C2PA (the Coalition for Content Provenance and Authenticity) is an initiative aimed at establishing technical standards for the provenance and authenticity of media content through the use of meta data captured at the point of creation and cryptographic signatures to ensure that any changes to the provenance information are detectable. The standards are designed to be interoperable across different platforms and tools, ensuring broad adoption and usability. To quote the BBC (an early adopter), C2PA is “information (or signals) that shows where a piece of media has come from and how it’s been edited. Like an audit trail or a history, these signals are called ‘content credentials’.”

While C2PA is interoperable in principle, a lot of the standards are being driven by the large entities. If you look at who (or what) is part of the C2PA consortium, it’s a lot of technology companies, a few large media agencies and some high-end camera makers. If you can buy the new Leica digital cameras, pay for your team to have Adobe accounts, be part of the BBC or Reuters, or so forth, you’re on track for your work to have digital signatures and blockchain records tracking is veracity. You can show your homework and be trusted, if you can afford to do it.

There is an inherent threat of gate keeping in this. The people on the front lines capturing the footage are often the least resourced. How will a global standard of authentication be made available to the local, independent journalists operating without the latest, greatest hardware or access to Creative Suite subscriptions? Putting language and localisation aside for just a moment (as it all too often is) there are economic hurdles to being believed. While it’s great the the BBC and CNN will have instantaneous evidence that their material is authentic, they aren’t actually the most attacked groups on this front. It’s the Burmese media activists recording police brutality. It’s the Palestinians gathering evidence of daily war crimes in Gaza on their mobile phones. It’s the Sudanese journalists capturing brutal actions by the regime and its foe, the Rapid Support Forces paramilitary. It’s anyone capturing evidence of China’s crimes against humanity against Uyghurs. The list goes on, the world is on fire and the media recording it all is aggressively attacked all the time.

Much like the tools that can generate artificial content, access to the methods that establish origin will not be evenly distributed. Money, language, usability, interoperability (or the lack of these) will create barriers for many information providers who could benefit the most.

Taking a stab at C2PA for the rest of us has been The Guardian Project‘s ProofMode work, which late last year announced its new Simple C2PA development. The goal of this is to bring the various benefits of C2PA provenance actions and signatures to an implementable code library that developers of mobile phone media apps can incorporate and run on Android or other devices. The world is still on Android. If C2PA is going to mean anything, it needs to be widely adopted, and this entails being accessible across economic levels. Without this, you end up with believability being a luxury good for the well-funded, and it will be easier for those attacking media workers who can’t buy their way in, by pointing to their lack of meeting the standards. Like everything else, provenance is a class war issue.

In April this year the Coalition for Content Provenance and Authenticity also had representation at the International Journalism Festival in Perugia, Italy. In a crammed session folks from Microsoft, Witness and the Partnership on AI focused not just on the importance of showing authenticity, but something that’s the flip side of the same coin: how should generated content also be marked? AI tool adoption in newsrooms is taking off much faster than the guidance around how they should be used can keep up.

In a year in which Netflix aired a crime documentary that mixed generative AI material with archival footage without informing viewers, the provenance of what is manufactured is as important to show as what’s been captured by humans. The potential for controversy around this is big. Microsoft, one company that sees big profits in selling AI tools, has launched a Content Integrity Initiative for Newsrooms to get out in front of it, though aimed more at users of its own products. In a more platform agnostic approach for how to ethically mark generative AI in documentary films, the Archival Producers Alliance has been working on Generative AI guidance of its own.

There are two core challenges to viable provenance:

- Transparency: Our working definition here is that the media’s creation can be clearly traced back to its point of origin, with modifications timestamped and described along the way, in a way anyone interacting with it could access and follow.

- Persistency: This is about the durability of the proof of the media’s creation source. Once created, video, images or text will travel far and wide. When the media is re-used, copied, cropped or changed in some way and re-shared (either with the creator’s consent or not), the issue to tackle is how some proof of origin can travel with it.

To different degrees, these remain unsolved problems. So long as a a piece of media is used by legitimate sources, the transparency and persistency can remain unbroken. The challenge is when people re-use a piece of media, change it for their own purposes, or reshare it in other contexts. But technical layers that demonstrate provability can only take things so far. “The whole fear about ChatGPT and the creation of imagery is, I think, fear based on the fact that we live in a world where everything is up for grabs,” said the ‘Thin Blue Line’ documentary filmmaker Errol Morris in a Neiman Journalism Lab interview. “You’re trying to establish something that represents the real world,” he said elsewhere in the same piece. “And that’s not something that is handed over to you by style, whatever the style might be. It’s a pursuit. But I guess people are so afraid of being tricked or manipulated that they feel if they impose a set of rules, somehow they don’t have to be afraid anymore. I would like to assure them that they still need to be afraid.”

Instead of afraid, we could shoot for enabled. C2PA has the core ingredients if it can be made usable. In a world where people are encouraged to go on auto-pilot using AI tools that themselves often don’t disclose where their source material comes from, being able to traceably prove origin is going to become a value proposition that’s beyond commodification. Though I’m sure people will try. The concern is who get priced out of being able to show their work.