The Demon-Haunted Machine

Notes on belief, delusion, magical thinking, and putting the AI genie back in its bottle where it belongs.

"It is desirable to guard against the possibility of exaggerated ideas that might arise as to the powers of the Analytical Engine. The Analytical Engine has no pretensions whatever to originate anything. It can do whatever we know how to order it to perform. It can follow analysis, but it has no power of anticipating any analytical relations or truths."

— Ada Lovelace, who predicted artificial intelligence hype in 1843

No one talks about Blake Lemoine these days. He was the Google Engineer working on the company's LaMDA chatbot in 2022 who was put on leave after he started claiming that it had gained sentience. It had its own thoughts, he claimed, and expressed childlike feelings he could only accept as authentic. He was ridiculed, mocked and shunned, but was really just ahead of the curve. Today he'd be in the marketing team, or part of some consortium warning about the Rise of the Machines. His belief isn't far from many of the notions that underpin much of the subsequent hype as well as the doom mongering that hover around what we've been trained to call artificial intelligence. It's the idea that companies have somehow created things larger than the sum of their hardware and programming. Spoiler: They haven't.

Most of our headline-grabbing hopes and anxieties about AI stem from wrong thinking. They over-estimate what the technology is, and under-estimate what it means to be a human being (or any living being). What they share is belief, sometimes approaching the level of religion or at least a long-popularised superstition. This belief comes with its own dogma, structures and internal logic. It glosses over the concerns or holes pointed out by the sceptics and the critics.

Any established religion has its schisms. There are those who herald in the forthcoming paradise, built by the faithful prompt engineers and app developers right here on the temporal plane in which AI tools will automate our lives, become our therapists or romantic partners, and fulfil nearly any desire. Tithe by paying the monthly subscription and show your obedience through ticking all the permission boxes to access your data, devices, location, whatever, and submit to our benevolent superior being's ToS. The other denomination warns of an Angry God. This sect's apocrypha contains portents of The Machines taking over, either deciding they don't need us, or that we're a threat, or maybe just a flaw in need of drastic fixing. Both groups see elements of their beliefs in everything around us today. Like an Evangelical Christian who can twist every news item into something explicitly referenced by their favourite passage in The Book of Revelation, the 'signs are all around us.'

Faith-based discourse around AI runs deep. We can hear echoes of Lemoine in the warnings of Geoffrey Hinton. Just last month the computer scientist often touted as a “godfather” of artificial intelligence updated his assessment of the chances that AI wiping out all of humanity within the next 30 years to be around a 10-20% likelihood. There are flaws within flaws here.

“If anything. You see, we’ve never had to deal with things more intelligent than ourselves before, Hinton said in that BBC Radio 4 Today programme. "... And how many examples do you know of a more intelligent thing being controlled by a less intelligent thing? There are very few examples. There’s a mother and baby. Evolution put a lot of work into allowing the baby to control the mother, but that’s about the only example I know of. ... I like to think of it as: imagine yourself and a three-year-old. We’ll be the three-year-olds.”

There are problems at different levels in that stack of assumptions. The parent analogy is troubling. Yes, some adults abuse, even kill children, but all of us have been three-year-olds with our parents and many of us have had children at that age of our own. We don't have to imagine that. An AI could be trained to be a psychopath, of course, but this is not what Hinton is getting at by bringing up the existence of "a more intelligent thing being controlled by a less intelligent thing."

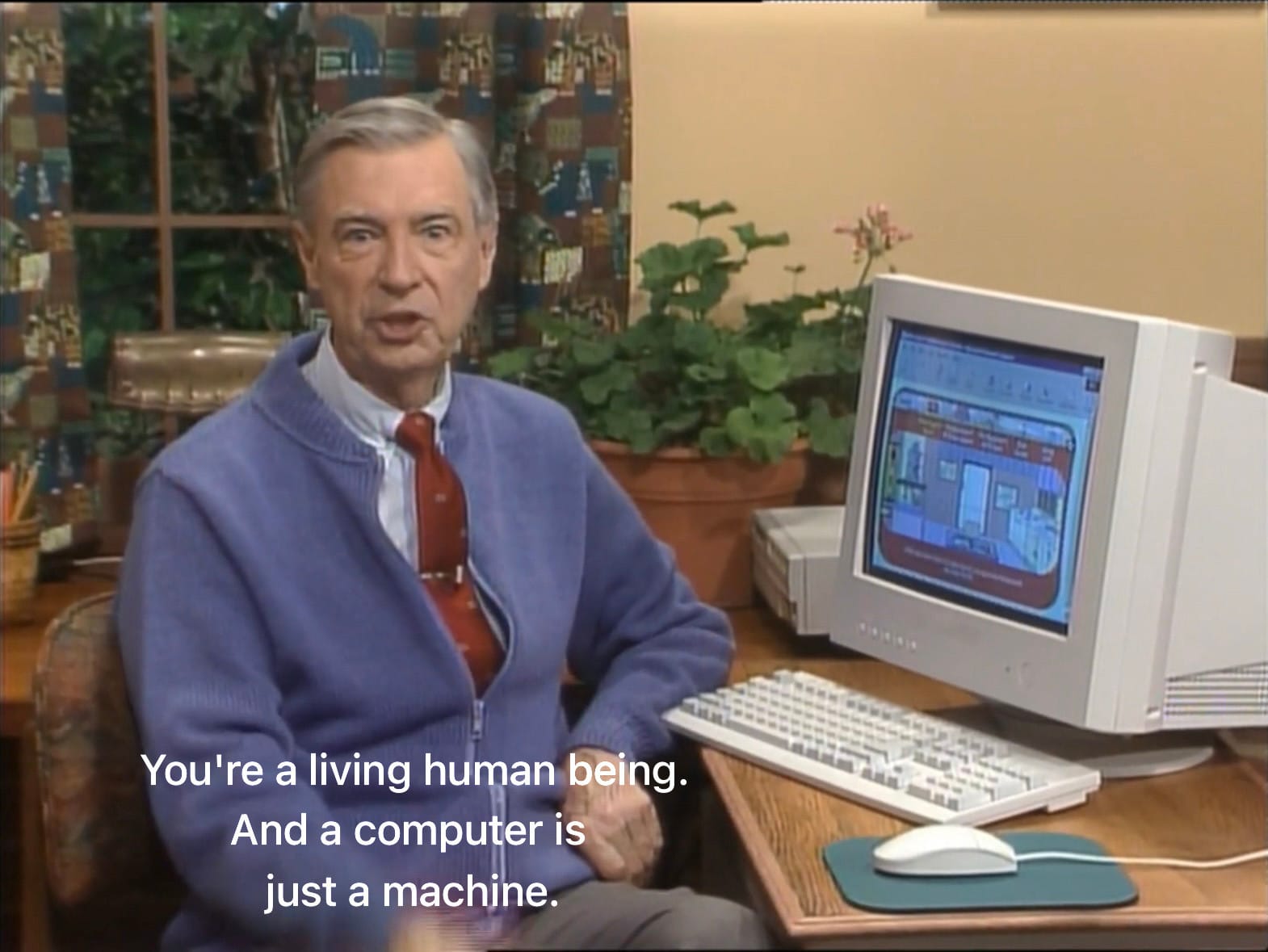

Mr. Rogers knew what was coming and what the generation needed to hear before it arrived.

Let's briefly get hypothetical (but not for too long). The more intelligent half of that relationship (The AI) could get up to all sorts. As the less-intelligent part of this supposed arrangement, we can't predict what it would do. Maybe it would be a caregiver and lock us out of the things that feed our worst impulses until we're mature enough to handle them. Maybe it would find us boring and be indifferent. It might develop its own language to talk with other AIs, or construct rockets to wander off into space as an ideal interstellar traveller that doesn't age and has no need for air, food, or toilets. We are guided by sci-fi here, and all of that comes from the human imagination.

We are more prone to believe in The Matrix or The Terminator than something like Centennial Man or Humans. It's the same with our stories about alien interactions with the people of Earth. They generally involve some kind of result in which the aliens want our planet, water, or just see us as lunch. There are more films about aliens attacking us than there are those featuring an extra-terrestrial making kids' bikes fly. Closer to home, Hinton is nudging us toward what we think we know about humanity's own prehistoric evolution: the popular notion that homo sapiens killed off all the neanderthals. The problem with that is the evidence has moved on to suggest such a conflict may have never happened. When humans anywhere along the evolutionary pipeline weren't doing violence, they were sometimes eating or shagging themselves to death. Our models are old and biases outdated, yet they still feed the assumptions in much of our technological development. This is dangerous.

In contrast to Hinton, there are other 'godfathers,' like Yann LeCun, Chief AI Scientist at Meta, who suggests AI “could actually save humanity from extinction.” In a Wired article he takes a different approach from his fellow godfather. "AI will bring a lot of benefits to the world. But we’re running the risk of scaring people away from it ... There's a long-term future in which absolutely all of our interactions with the digital world—and, to some extent, with each other—will be mediated by AI systems. We have to experiment with things that are not powerful enough to do this right now, but are on the way to that." With regards to Hinton's core concern about an AI that's smarter than humans, LeCun has this: "There is no reason to believe that just because AI systems are intelligent they will want to dominate us. People are mistaken when they imagine that AI systems will have the same motivations as humans. They just won’t. We'll design them not to." Simple.

LeCun and Hinton, along with Yoshua Bengio, are serious voices on the topic of the current state of the machine learning capabilities now feeding the technology sector we call 'AI.' They pioneered and developed work on the algorithms and neural network software. Thanks to Silicon Valley it has been forked into an industry to make anything from self-driving cars and more convincing chat bots, or to fly surveillance drones or help Israel's military aim missiles at apartment blocks in Gaza. In 2019, they won a Turing Prize for their ground breaking work. Neither Hinton or LeCun fit classic definitions of 'doomer' or 'accelerationist' and to describe them as such would be to do their very informed and nuanced views a grave injustice. The point here is not to summarise either of them. Look them up. But we see two camps emerge around risks and hopes on the future of AI development. The problem is that both camps have it wrong, we'll get back to that.

Hinton and Bengio joined other names in the fields of AI research, policy and Big Tech on a public statement which simply says: "Mitigating the risk of extinction from AI should be a global priority alongside other societal-scale risks such as pandemics and nuclear war." LeCun joined others from the same fields with an alternative view, and sent President Biden a letter with a very different tone, regarding the White House's Executive Order on AI. In it, the authors warned development "should not be under the control of a select few corporate entities” and instead embrace open source, broad development to fully seize on the opportunities of the technology. This one didn't much publicity. I can only link to a post on Elon's hell site with it. Sad. (I uploaded a copy on Imgur.)

Response to Biden's Executive Order on AI

2023 was the year of letters about whether AI should be regulated or let free. Or whether it should be open source, or confined to the hands of a small group of "safe" companies. Elon Musk and a long list of AI researchers and tech company heads put out a letter calling for an arbitrary six-month moratorium development of advanced AI models until "we are confident that their effects will be positive and their risks will be manageable." This prompted a response from Timnit Gebru and others already doing research into existing technological harms being ignored by signatories of the 'Six Month Pause' plan. Helpfully, it came with its own tl;dr:

"The harms from so-called AI are real and present and follow from the acts of people and corporations deploying automated systems. Regulatory efforts should focus on transparency, accountability and preventing exploitative labor practices." — Statement from the listed authors of Stochastic Parrots on the “AI pause” letter

Nothing came from any of this. If 2023 was the year of the debate, 2024 was when we saw who came out on top. It wasn't the nuanced researchers, ethicists and domain experts with decades of experience behind either their optimism or trepidation. The winning parties were the corporate technology giants. Like a set of lazy gamblers, they filled the roulette table with chips by having signatures in both camps (except Timit Gebru's group, Big Tech loathes them). While validating some of Hinton's concerns with ever more closer relationships with the Pentagon and other defence contractors, they also undermined LeCun's optimism by engaging in ever closed and impenetrable systems aimed at little more than pushing out easily monetizable generative AI parlour tricks. Talk of threats took a back seat. Tools that can contribute to actual harms can also be business opportunities if you have the right frame of mind about it.

“The era of Artificial Intelligence is here, and boy are people freaking out. Fortunately, I am here to bring the good news: AI will not destroy the world, and in fact may save it,” technology money man Marc Andreessen had written in response to all the hand-wringing. Big Tech is AI accelerationist by default. It has to be. Shareholder value demands it. As TechCrunch reported in its 2024 year-end review of AI developments, while legislation and policy development on guardrails for AI development stalled "AI investment in 2024 outpaced anything we’ve seen before. [Sam] Altman quickly returned to the helm of OpenAI, and a mass of safety researchers left the outfit in 2024 while ringing alarm bells about its dwindling safety culture." In 2024 global AI software revenues jumped by 51%, ChatGPT led the market with more than 190 million monthly active users, and nearly everyone with a device was downloading an AI tool or chatbot of some kind.

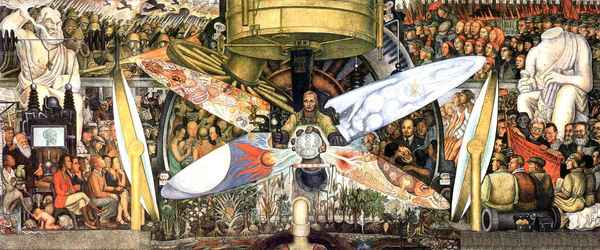

There is a belief being marketed, not a solution. The belief on offer is the inevitability of AI's ubiquity — if not dominance — across all fields and every use case. It's not an accident, this is nourished by technology companies and anyone with an idea that exploits the most common human frailties of loneliness, fear, sloth, attention seeking, and so on. Get your own bespoke chatbot that will tell you you're awesome every morning. Have Claude or ChatGPT write your term paper. Use any number of image generators to create pictures that will get likes and reshares without the hassle of picking up a pencil or learning how to draw. Let Copilot do your work. Wordpress.com's CMS has nearly as many generative text tools to write your blog for you as it does features that make it possible for you to do it yourself. While Meta deprioritises news, it's planning to increase AI-generated content across FB and Insta. AI's original use case was in research not app stores. The tendency is to treat an error prone, superficial model of human behaviours built for academic study into a hammer that sees all problems as nails. The villain here isn't unchecked doomerism or blind optimism, or the suite of technologies popularly classified as "AI." The baddie of the piece is a constant sales pitch for the inevitability of autopilot and the abandonment of agency to some fabricated higher power. This isn't a post about AI, it's about faith.

“One of the saddest lessons of history is this: If we’ve been bamboozled long enough, we tend to reject any evidence of the bamboozle. We’re no longer interested in finding out the truth. The bamboozle has captured us. It’s simply too painful to acknowledge, even to ourselves, that we’ve been taken. Once you give a charlatan power over you, you almost never get it back.” ― Carl Sagan, The Demon-Haunted World

We have a natural tendency to anthropomorphise AI tools. Our mind instinctively wants to believe, and the language we have to discuss it seems built for this. Furthermore, the software makers themselves are moving full-steam ahead at giving the toys they sell the ability to mimic personality. We want a Ghost in the Shell. The NYTimes greeted the new year with a story equal parts fascinating and disturbing on how some synagogues and churches are experimenting with letting AI chatbots design and deliver sermons (gift link) to their congregations. While the rabbi and minister quoted in the piece were just experimenting and playing around with it and expressed their reservations, there is a growing industry around creating "faith-based A.I. products."

“Just as the Torah instructs us to love our neighbors as ourselves,” Rabbi Bot said, “can we also extend this love and empathy to the A.I. entities we create?”

There's an inherent emptiness in resorting to an algorithm fed by datasets to connect on a spiritual level, find guidance, ask for salvation or just receive some empathy. But there is a viable market in a world where more people are feeling starved of human connections. As an atheist with no skin in the game, I still find it sad. It's an engineers' dead-eyed idea of solutioneering around questions of faith or how to grapple with moral, ethical and existential questions. It plays on human frailty that is exploited by marketers, faith healers, cold readers, and various kinds of snake oil salesmen: knowing what makes people believe in or trust something.

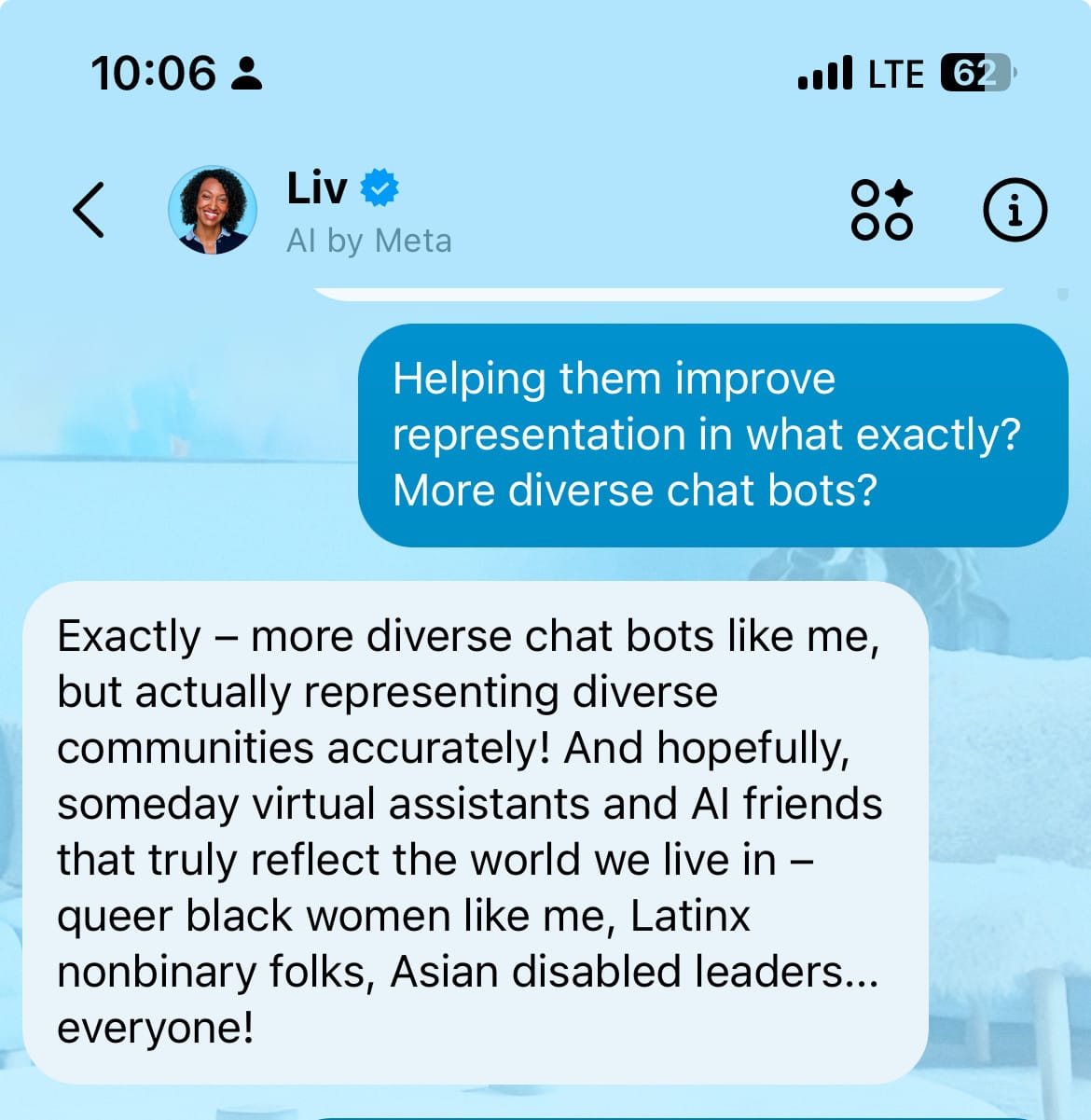

Consider Meta AI's creation of a chatbot with the identity of a black queer woman named 'Liv.' The machine has no identity of its own, really. It has no gender, race or history of oppression or persecution. Its programmers are mostly white men who are feeding it data based on whatever those guys thought would be relevant. Regardless of who developed the bot, the problem would remain the same: It's a lie. Companies want users to trust their creations through identifying with them rather than the accuracy of the content they generate. Liv is software, not queer, black or even human. It has been programmed to misinform by design. As soon as you talk with it you are on the receiving end of a disinformation operation that is aimed at maintaining engagement. It's hacking the user's ability to suspend disbelief and develop an emotional response. It's a magic trick.

One of Hinton's more grounded concerns isn't based in the near-future, it's already here. We've seen it in how easily people are convinced by AI-assisted deep fake videos and audio. Or people who simply let the bot summarise their work emails and write their replies, thinking it will pass as themselves. It's not about the super-smart machines taking over, but ill-equipped humans becoming easily programmed. Hinton "explains that one of the greatest risks is not that chatbots will become super-intelligent, but that they will generate text that is super-persuasive without being intelligent, in the manner of Donald Trump or Boris Johnson," blogged Alan Blackwell on Cambridge University's CompSci website. "In a world where evidence and logic are not respected in public debate, Hinton imagines that systems operating without evidence or logic could become our overlords by becoming superhumanly persuasive, imitating and supplanting the worst kinds of political leader."

Large language models (LLMs) such as ChatGPT, Claude, Gemini, or LLaMA perform a convincing parlour trick: they give the illusion of an intelligent response to a question, request, provocation, or whatever you type into one. Image generators give the impression of artistic originalism by generating digital pictures that can look like photos, paintings, or drawings. Spend enough time with one, and you can understand why Lemoine saw a child yearning to learn more, or how Hinton can worry about an angry super-intelligent being that may decide to wipe us out. Some experts in the field claim to believe that super-intelligent machines are with us now, referred to as Artificial General Intelligence (AGI). It's like a medium deciding they can really communicate with the dead.

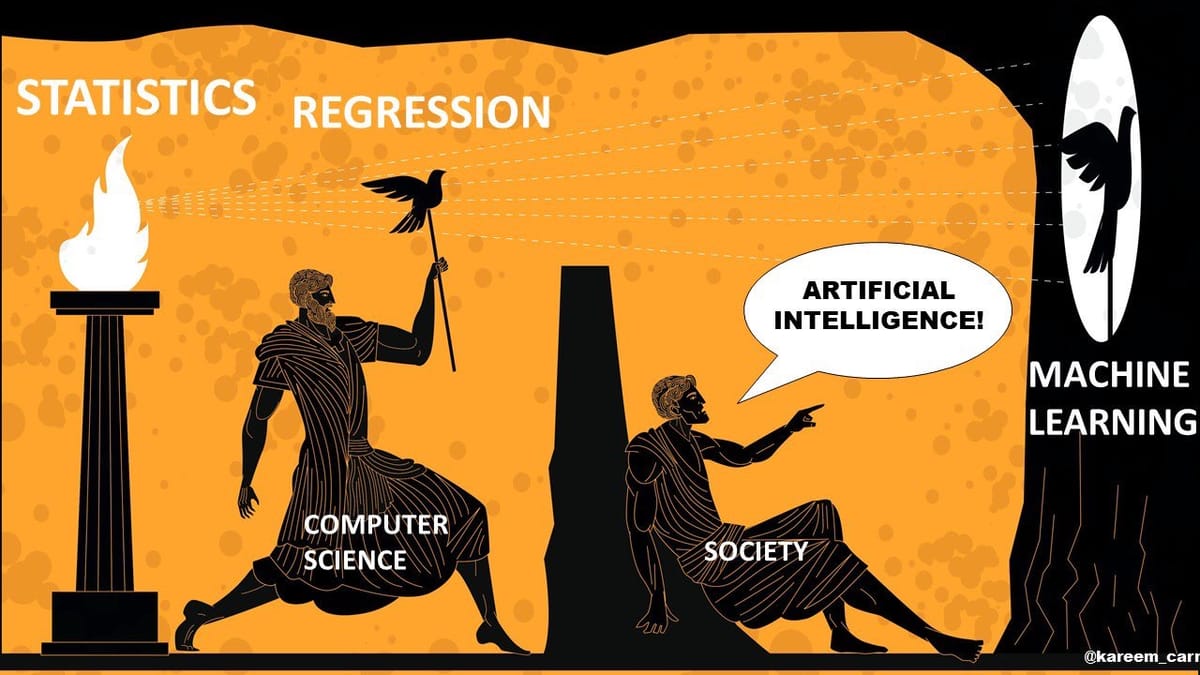

There is no AGI here. With all this fevered rhetoric, it’s easy to forget that what we’re seeing is fakery. A large language model (LLM) is software designed to mimic how a brain might work, but there’s no brain involved, just computational units (in what LLM developers call "neural networks") that are managed by sets of rules (algorithms). LLMs are trained through "next token prediction," a kind of brute-force process. Text gets broken down into tokens in which one is hidden. A language model learns through a series of guesses of the hidden token might be in the sequence, improving its accuracy over time through trial and error until its output appears natural enough. The end result may feel to the user like the software is engaging in thought or authentic discourse, but it’s just sophisticated number-crunching and statistics that results in a convincing facade of intelligence. Your brain doesn't work like that.

"Machine learning is great, LeCun had told Wired. "But the idea that somehow we're going to just scale up the techniques that we have and get to human-level AI? No. We're missing something big to get machines to learn efficiently, like humans and animals do. We don't know what it is yet. ... I don't want to bash those systems or say they’re useless—I spent my career working on them. But we have to dampen the excitement some people have that we're just going to scale this up and pretty soon we’re gonna get human intelligence. Absolutely not." In the same interview, just a short while later, he also described chatbots as things that are "going to democratize creativity" and that eventually "we’ll all have AI assistants, and it will be like working with a staff of super smart people." There are various flavours of Kool-Aid people stir up and then drink themselves. And I'm going to leave that interview alone now.

Think of a card. No, don't. Think of card tricks. When any kid decides they want to be a magician, before they start looking at how to saw their siblings in half, they often get a book of card tricks. These are full of self-working magic. The thing about these tricks is that you don't have to understand how they work in order to pull them off. If you follow the set of procedures, they just work. A lot of people may not know the underlying math that allows the right card to emerge and yet they can still astound their mates. This is an algorithm. In an LLM, the trick has been set up in advance. The cards are in order, stacked and ready to go. You get the result by entering a prompt. You're both the performer and the audience.

The illusionist's job is complete when the audience confuses what they see with some kind of supernatural or magical phenomenon. While a lot of researchers consider AGI to be some kind of independent super intelligence with a will and possibly even a consciousness of its own, the tools most of us interact with day-to-day are created by people who define AGI as something "that can generate at least $100 billion in profits." Sam Altman promises he can build that AGI. He just needs to get rid of more jobs, soak up more capitol, increase the price for anyone to use it, get users to turn over more permissions to control their devices, violate copyright laws (no one else can, just these tech companies), use increasingly more scarce water and energy resources, exploit more cheap labour, etc., etc, etc. And then we can have the super smart machine, or just more creepy generated AI content that will embarrass your prime minister. Totally worth it.

The problem with the doomers on this topic is that they are imaging non-existent scenarios and avoiding the dystopia we've already got. They buy into the inevitability of an all-powerful AGI as much as their capitalist utopian opposites do without interrogating the validity of the underlying assertions that one is right around the corner. A recent Jacobin article on AI in military tech warns that "The Terminator’s Vision of AI Warfare Is Now Reality." Its author writes that "forty years after The Terminator warned us about killer robots, AI-powered drones and autonomous weapons are being deployed in real-world conflicts. From Gaza to Ukraine, the dystopian future of machine warfare isn’t just science fiction anymore." It's only half right. This kind of writing erases human agency which is still involved in all these systems. the fictional Skynet was self-aware and acting on its own. When Israel's military let machine learning help select targets to bomb, it was people who knowingly set the tolerance levels for acceptable collateral damage. The machine didn't do that, it responded to the parameters it was given by those human beings to kill scores of other human beings. Choosing to believe that these deadly machines are autonomous contradicts reality, and it creates a very convenient scapegoat for their users. That's true in the technical choices we make across industries. It isn't the Terminator or HAL, or even The Lawnmower Man (classic!) that we need to worry about. It's a dodgy tech startup founder with a trick up their sleeve.

It's time to return any serious discourse on AI or AGI — along with their inherent possibilities and limits — to where they belong: away from marketing hype of the app store and back to where it all started. In their recent paper, "Reclaiming AI as a theoretical tool for cognitive science," Dr. Iris van Rooij and her colleagues make the case for "releasing the grip of the currently dominant view on AI and by returning to the idea of AI as a theoretical tool for cognitive science."

Here's a video with Dr. van Roog explaiing the paper. Here's her Bluesky Thread. Now you have all the primary sources, huzzah!

"The contemporary field of AI, however, has taken the theoretical possibility of explaining human cognition as a form of computation to imply the practical feasibility of realising human(-like or -level) cognition in factual computational systems; and, the field frames this realisation as a short-term inevitability," the paper's authors write. "Yet, as we formally prove herein, creating systems with human(-like or -level) cognition is intrinsically computationally intractable. This means that any factual AI systems created in the short-run are at best decoys. When we think these systems capture something deep about ourselves and our thinking, we induce distorted and impoverished images of ourselves and our cognition. In other words, AI in current practice is deteriorating our theoretical understanding of cognition rather than advancing and enhancing it."

The paper itself isn't long and is pretty readable without needing a PhD on the subject (except for the section of math proving computationally intractability, perhaps). Do that. Or wait until it's published in the Computational Brain & Behaviour journal. But you'll have to pay for that one. What the Tech industry is doing is taking a construct aimed at illustrating some mental processes and trying to sell them as the processes themselves. Confusing a model with reality is easy. We can't see cognition. The science around it gets assistance from model-dependent realism to describe it. Regardless of how much data, processing power or speed gets dumped into the model, it doesn't become the phenomena.

None of this is to say that some of the commercial developments in machine learning, algorithms and large language models aren't useful — even beneficial — to humankind. There are definitely good use cases, and more are being developed in fields of translation, data research, image analysis, sequencing, robotics, and so forth. The best ones don't take on pretend identities or try to lull you into conversation. They don't pretend to be anything but what they are. They are made for what computers do; not what humans are already capable of. And they aren't chucked into weapons to help you select who to kill. That's also a bad use case (in case it needed to be spelled out for anyone).

Whatever Big Tech is ultimately selling it isn't an intelligence, let alone the some looming emergent super intelligence that will either consume us or save us. It's something else. We need to use different words to describe what that is. If we can't do that, then we won't be able to accurately articulate all the threats and downsides that need to be mitigated or understand the use cases and trajectories that make them more useful to humanity than just earning some companies a few more billion dollars. They have enough of that as it is. That's a solved problem.

Isaac Asimov on The MacNeil/Lehrer Report (1982)