Surveillance capitalism is also just regular old surveillance

This post is migrated from the old Wordpress blog. Some things may be broken.

Tl;dr: Surveillance is a natural outcome of the internet as it was created. Surveillance capitalism isn’t an innovation, but a resource extraction industry, and states don’t need to make fancy tools to get a lot of information on dissidents or undesirables, they just need a budget line to buy it.

404 Media reported that a woman recently took online sex toy retailer Adam and Eve to court for handing over to Google the data about her searches for dildos and strap-on harnesses. The case argues that by disclosing her “sexual preferences, sexual orientation, sexual practices, sexual fetishes, sex toy preferences, lubricant preferences, and search terms” without her consent as well as her IP address since the site wasn’t using Google Analytics’ anonymized IP options. I kind of wonder if the site had “no-bid” response to Real-Time Bidding requests. I’ll bet it doesn’t, which would mean that this data could also be passed on to any number of data brokers as well. And then anyone can buy it.

Remember when the Snowden leaks dropped? Back in 2013 the world was smacked with the reality that governments had gamed the internet against everyone. There was a brief period of intense debate about mass surveillance and then it went away. One thing that it also did was install a piece of wrong thinking in the public: that government surveillance was somehow different and separate from the kind of practices used for things like targeted marketing. It also conveyed this idea that surveillance tech was somehow more sophisticated and required special software and deep technological knowledge. This was then reinforced by the news of spyware firms like Italy’s Hacking Team or some years later, the Israel-based NSO Group. These companies utilised lucrative 0day exploits to craft highly customised spy software that could game you entire device to spy on you. This was true, but within this coverage was some inherent propaganda: that targeted surveillance was a high-cost, high precision game, and maybe only a risk to a small group of individuals. This is not the case. For most of us, the state doesn’t need to invest that much. We are the lower hanging fruit.

Digital surveillance is not that hard, and can be more widely deployed against larger groups of people. The software and hardware are not difficult to come by, everyone has them already. People have mobiles and web browsers. They visit websites that try to make money by selling advertising. All you need to target your undesirables, your dissidents or opponents is a budget line to buy the data.

Real-Time Bidding

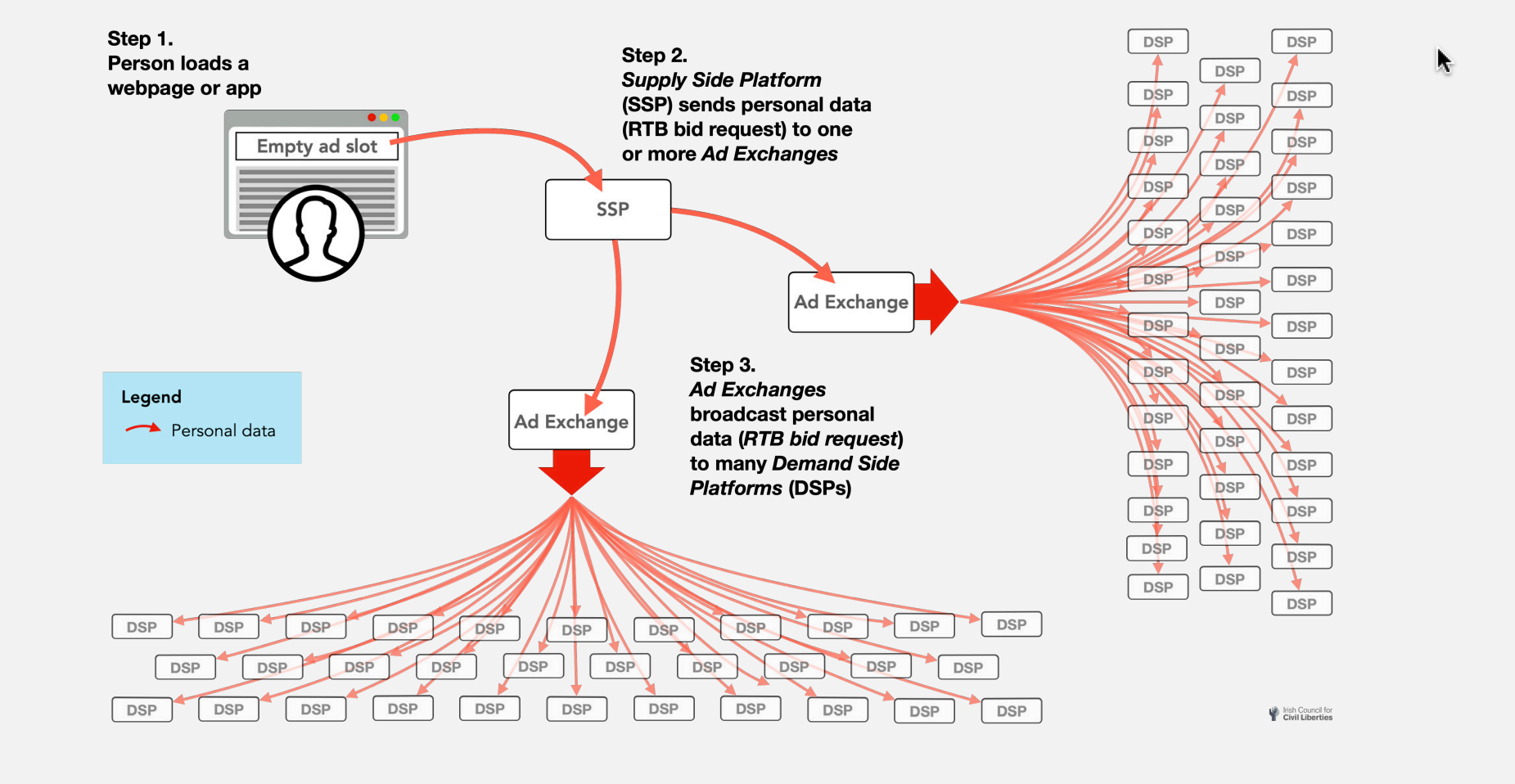

Late last year, the Irish Council for Civil Liberties (ICCL) dropped a couple of reports on how loosely any website user’s data can be collected (ostensibly for marketing purposes), analysed and turned into weapons. I’ve just been recently reading these, because I’m slow. The twin reports have similar sounding names: Europe’s hidden security crisis, and America’s hidden security crisis. Both are essentially the same report only with slightly different geographies and focused on how data about either defence personnel or political leaders can easily flow “to foreign states and non-state actors” via a mechanism known as Real-Time Bidding. While they aren’t necessarily “breaking news,” they expose key infrastructual realities about how data gets collected, stored, accessed, used, leaked, sold and exploited in entirely mundane ways that people don’t really clock as the security problem that is really is. We have been trained to expect the toe flexer adverts in our Instagram somehow showing up in the sidebar of some favourite news website, or how suddenly the kitchen appliance link you clicked on while reading a recipe is now recommended to you on Amazon. And we think “that’s just the algorithm” showing us what we like. But it’s not. Not entirely.

Real-Time Bidding (RTB) is advertising tech. It runs across millions of websites, from the very small to the sized that’s monetised through ads in some way. It’s in your news sites, social networks, dating apps, mobile games, email services, porn sites, and so on and so forth. Google operates RTB as does Microsoft and loads of others, including a number of less reputable companies. RTB involves the instantaneous broadcasting of what a user is doing on a platform to an untold number of other entities to provide an endless rapid-fire stream of auctions over which advertisement to put in slap in front of them. It’s also useful for building huge user profiles, or very specific, niche user profiles. From here the many problems flow. Not everyone in the auction is there to sell shoes or home aerobics equipment. Some of them are companies that just want the data to sell to anyone. Some of the customers that by it are governments.

The use of micro-targeting online behaviour in political campaigns is not new. Howard Dean’s failed 2004 presidential bid is generally credited with taking politics into the web. It was innovative in its use of social networks for community building, fundraising and campaign advertising, but also in how to understand people based on how they engaged online. Dean may not have one the White House, but his campaign set a new standard, and the people who ran his online work went on to create Blue State Digital, which went on to help make Barak Obama president. It is arguable that Blue State Digital is a progenitor to Cambridge Analytica, which was populated by the folks who helped sell Trump and Brexit. People who don’t like that take will point out all kinds of ways the two are not alike, but when you realise that both used the same data scraping mechanisms and murky loopholes that don’t require user consent, that debate gets a bit theoretical. In short: they’re wrong. It’s all just iterations on top of one another. All these companies will argue they’ve broke no laws. They’re probably right. That’s the problem. The structures that allow them to be legal but ethically dubious allow for illicit purposes, and regulating any of it is bound to essentially break the online advertising model itself. Internet advertising services — at large scale — is dependent on the low friction transmission of detailed user data.

While ICCL’s reports are particularly concerned about RTB-enabled foreign access to sensitive personal data about EU or U.S. political or defence leaders, I’d argue there are far greater concerns for at-risk groups, the already marginalised, the dissidents, those in media and civil society and so forth The data can be used to spy on target individuals’ financial problems, mental state, and compromising intimate secrets. The potential threat posed by the misuse of RTB extends t a wide range of individuals, including political dissidents, asylum seekers, opposition candidates, and members of the LGBTQ+ community. The widespread trade in RTB data about sensitive individuals exposes them to blackmail, hacking, legal prosecution in their home jurisdictions whatever else a regime wants to do with it.

Private surveillance companies are also collecting RTB data, not for selling ads, but to sell the data itself, or just to operationalise it. Near Intelligence and ISA reportedly obtained masses of RTB data directly from ad exchanges through their own DSPs. Near Intelligence claimed to have used this data to profile millions of Europeans, including their home locations and places frequented. Similarly, ISA Security acknowledged obtaining RTB data indirectly via major firms to power its “Patternz” surveillance operations. More directly, the ICCL’s report found that Google and other RTB firms send RTB data to Russia and China, where national laws enable security agencies to access the data.

Data brokerage is not new, but few are aware how wide the selling and reselling of it is, and how targeted it really is. In a recent example covered by Wired, Near Intelligence RTB data showed the data trail of nearly 200 devices that at one point were present on the island owned by Jeffrey Epstein, notorious for its links in sex trafficking of minors. A lot of people may look at this and say, ‘well that’s not a problem.’ Except it is. These kinds of examples get the bigger news coverage, but they are problematic. No one cares if people involved in Epstein’s illegal activities get caught through their data, a number of people may even applaud it.

But data brokers are like any mass surveillance operations. They pull down everyone’s data and slice it into different mixtures for different buyers. Maybe the feds are interested in who was friends with Epstein. A company fronting for Russia may be more interested in where the dissidents are hanging out in London. One in China may be interested in what kinds of sites the Hong Kong protest leaders are checking out. Previous to it’s latest report, ICCL had shown that RTB data was used to target LGBTQ+ people ahead of 2019 Polish Parliamentary elections a data, and broker had illicitly profiled Black Lives Matters protesters in the U.S. Data brokers can create profiles that can be narrowed down very specifically. So, a customer could focus on who is profiled in a “Substance abuse” category, or with other health condition profiles to include “Diabetes,” “Chronic Pain” and “Sleep Disorders.” etc. Maybe you’re more interested in an “AIDS & HIV” category, or those who are searching for resources on “Incest & Abuse Support,” “Brain Tumor,” “Incontinence” and “Depression.” Data brokers keep user profiles on all of these things. Real-time bidding data is at the same time mass surveillance that can easily be narrowed down into very targeted surveillance.

NSO Group’s Pegasus spyware captures the imagination because it seems to be able to infect a mobile device without the user really doing anything. NSO Group, in my opinion, benefits from the inherent marketing that comes with the notorious coverage of its products. But there’s another more mundane Israeli digital surveillance company, ISA Security, that seldom gets the limelight, but arguably had a much more attractive return on investment for a number of clients through its Patternz product, which relied on Real-Time Bidding data to do its job. Before coverage led Google into cutting its data access, Patternz had records on nearly 5 billion user IDs.

There is no opt out

It’s good that ICCL is pursuing this at a policy level in courts because GDPR-complient pop-up boxes and ad bocker plugins are not going to cut it, there’s too much money on the line. Companies like Meta will go out of their way to buy and promote a privacy tool that in fact just collects more data on its users. Google’s Chrome browser is going to start blocking access this year to tools that disable some of the most invasive elements in adware. And those GDPR-required cookie opt-out workflows are often purposefully annoying and misleading to get users to make choices they didn’t intend. From a technical point of view, there is no long-term solution. The internet was not built with security or privacy in mind, these have been layered on with a succession of iterative protocols. In turn, they’ve been challenged with a continual line of web products both more fun and in many ways useful but each requiring an increasing amount of surrender. People want to play some games and share some photos. Our very nature works against us. It’s not that you don’t have anything to hide, but dwindling control over what you want to disclose. Happy Easter.