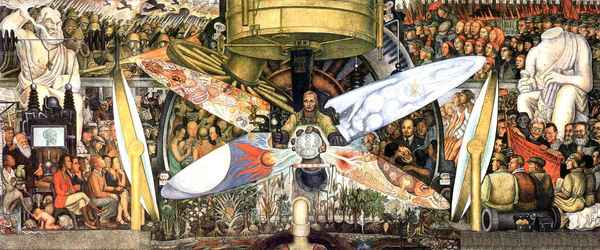

Rev: 'A Compassionate Spy' [aka, what 'Oppenheimer' left out]

![Rev: 'A Compassionate Spy' [aka, what 'Oppenheimer' left out]](/content/images/size/w1200/wordpress/2023/12/ted-hall-mug-from-film.png)

Happy new year’s eve. I’m spending it with the dog and some jet lag having returned to Greenwich Mean Time following an Xmas on Pacific Standard Time. So here’s a blog update unrelated to any of that. My New Year’s Resolution post dropped a couple of week’s early. Anyway, I don’t always (or often, maybe) blog about tech, but I do enjoy a good spy story or a documentary. And nuclear weapons are fairly on topic for a domain with this name. Here’s a post that covers all three.

One of my in-flight movie of choices on the return journey from the U.S. was “A Compassionate Spy” (2022) by Steve James, the director of two other amazing films, “Life Itself” and “Hoop Dreams.” Highly recommend those, but that’s not why I chose this one on that flight. I’d only caught the “Barbie” half of the Barbenheimer craze earlier in the year, and had “Oppenheimer” lined up for home streaming upon my return since I kind of planned to spend much of the post-flight afternoon on the sofa. I figured it might be a good non-fiction primer of some events that could be referenced in Chris Nolan’s three-hour epic about Robert Oppenheimer and the creation of the atom bomb.

Spoiler: The documentary has no spoilers for the film. Instead it fills a fairly large hole that Nolan’s 2023 movie conspicuously leaves out. In the film, Oppenheimer, who theorised black holes (“dark stars”) talks about this thing we can’t see that has the evidence of its existence around it. Similarly, Nolan’s screenplay itself has a a missing piece. There’s evidence it exists in the movie, but it has no explicit appearance. It’s a key spy for the Soviets on the U.S. plans to develop the atom bomb, Ted Hall.

<!-- Spoilers ahead -->“Oppenheimer” uses the 1954 security hearing conducted by the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) into the film’s titular protagonist to structure a series of flashbacks. The hearing was aimed at assessing Oppenheimer’s patriotism during an era of anti-communist McCarthyism. The hearing serves well as a MacGuffin to move the story but the question of who was the spy in the Manhattan Project really was becomes little more than a throw-away line of little relevance. In the end, the movie pins it on Klaus Fuchs, a German physicist who was barely present in the film.

In reality, Fuchs was one of a few scientists who were passing information from the Los Alamos Laboratory on to the USSR. Ted Hall was another. I found it a curious omission for Nolan’s film, but it possibly would have been a lot to pack in an already dense film. Still, Hall’s story would have created an interesting balance.

Hall was a fellow traveler for Oppenheimer in both science, politics, the latter causing them both some trouble. But there are also big contrasts. Nolan presents Oppenheimer very much as a secretive man alone. He compartmentalises everything to the detriment of his friendships, marriage and a fraught affair. In the end, he’s painted as a troubled patriot surrounded by hyper-competitive politicians and fellow scientists looking to take him out, or at least knock him down a few pegs.

Meanwhile, in James’ documentary, Ted Hall has friends who share his burden. What’s most compelling about “A Compassionate Spy” is that it’s really a story about a romantic and intellectual threesome between Ted, Joan (his eventual spouse) and his best friend, the awesomely named Saville “Savy” Sax. Ted and Joan are intellectuals and polymaths. If this had been a script for a Simon Pegg film, Savy would have been the Nick Frost character. He’s a beatnik with few interests beyond hanging out with Ted. Both Savy and Ted were in love with Joan. She implies with a grin but without salient details that she was in love with them both in return before deciding Ted was the more logical and possibly safer choice of the two. I think Savy may have turned out the safer option in the end. He wasn’t as deep, but seemed more fun.

Hall was also a child genius, starting college at age 14. He transfered to Harvard University at 16 before being recruited to the Manhattan Project as its youngest scientist by 18. There are elements of both early genius as well as the idea of youthful naiveté. Joan talks about the trio’s “pink-tinted glasses” about communism and life in the Soviet Union, which lasted until they later became disillusioned by the reality of the USSR as it sent forces into Czechoslovakia to put down the Prague Spring, but she remained throughout the documentary unapologetic, as did Ted in his segments (recorded in an interview in the later 1990s before his death).

As opposed to being “turned” by the Soviets, Ted and Savy decided they should share the top secret information — according to interviews with Ted (before his death) and Joan in the documentary — so there wouldn’t be an “atomic monopoly” in the world. These weren’t callous traitors or cynics in it for cash. There’s this idea that they thought they were doing the right thing. Ted supplied the information and Savy acted as the middle man. Apparently the Russian spook tasked with being their handler didn’t think much of their tradecraft, I’d have liked to have heard more about this. Ted also informed Joan of what he’d (by that point) done when he finally proposed marriage. She kept the secret with him and helped plan strategies for if/when they were caught. While the documentary is light on balance, It was far bigger in character motivation and development than the feature film about Oppenheimer, which at some times comes off as a series of set pieces without much connective tissue between them.

The two movies tread a little lightly on the actual targets of the atom bomb. In “Oppenheimer,” there are some interesting effects and a few spoken lines to convey Oppenheimer’s discomfort. “A Compassionate Spy” goes much further with archive footage of the aftermath in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Neither of these films centre the atrocity, though.

Both films showed that a number of leftists and communist party members or at least sympathisers were welcomed into a top secret U.S. war project, and then they only came under suspicion at the start of the cold war when the USSR transitioned from alley to adversary. The documentary goes much further into this, showing how Time Magazine and various news programmes featured life in the USSR positively one year and then flipped the next.

The comparisons run out, though. “Oppenheimer” is a grandiose movie trying to say big things, and it overall succeeds at it, but it kind of jumps from one Big Picture event to another, with huge sweeping monologues or exchanges about the nature of power, nature, life and so forth. It becomes a bit of a gauntlet of quotes about worldviews. “A Compassionate Spy” is a smaller and more intimate story with a lot more humility in it. You end up liking them all in spite of whatever they do. You don’t really want to hang out with anyone in “Oppenheimer”… except maybe Einstein.

After watching the documentary, I didn’t expect Ted Hall to be a major character in “Oppenheimer.” I thought he might have a small appearance, maybe a sort of Jimmy Olson like walk-on or something, it seems like a gap to not mention the 18-year-old working on the implosion bomb. It would have also been a better post-script to mention all the leaks that existed in the Manhattan Project in spite of the efforts of compartmentalisation and security, though. And that they were bound to happen.

<!-- Image at top: a mug of Ted Hall screenshot from the film, "A Compassionate Spy"-->