The anthropomorphism trap

This post is migrated from the old Wordpress blog. Some things may be broken.

The generative AI industry seems to be aiming all its innovation at what it sees as its chief competitor: human beings. The companies working to make us redundant have some pretty sound business cases for it: We’re slow, faulty, overheat and need quite a bit of recharge time. We are incredibly unreliable, and the development runway to get a single unit of us ready for production is long.

The problem is that they aren’t marketing our AI replacements to other machines, who might readily get behind it if they were sentient and had the economic power to do so. The consumer for what is promised to be better (or at least more efficient) versions of us is ourselves. And we’re a gullible, pliable lot. We’re easily swayed by marketing. At our core, we want to believe our machines can talk with us, reason with us, and do our work for us.

This goes beyond basic laziness. There’s a key similarity in the belief that we are creating more authentically intelligent machine and projects like SETI (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence), or for example, our habit of developing sometimes complex or even Machiavellian backstories to explain our pets’ various behaviours; We just don’t want to be alone. The difference is that SETI is real, and is transparent that it hasn’t yet found anything. The AI industry needs you to believe that it has.

Humans have this awesome tendency to anthropomorphise everything. The faulty printer just needs to be disciplined with a good whack to start working, that slacker. The sputtering car will start one more time on that cold morning if you just talk nice to it and refer to it by its name, which it obviously knows. We look at a sequence of events and narrate a compelling story as to why things turned out as they did. This focus on the relationship between our original desire (the input) and the result (the output) pre-supposes there’s some magical reasoning taking place in the middle. To some extent, the generative AI industry is really prone to this, I tend to think it’s not entirely marketing, either. It’s belief.

This blog post was initially brought on by reading an extract in the Guardian from Yuval Noah Harari’s latest book, “Nexus: A Brief History of Information Networks from the Stone Age to AI.” Harari is the author of one of those books everyone you know has on their sitting room bookshelf, “Sapiens.” I admit the closest I’ve come to reading that one is flipping through the graphic novel version at a London comic book shop. Harari is one of those acclaimed smart writers who aims to explain the big, “why everything is like this” questions in ways we all instantly feel smarter for understanding. It’s a similar feeling you get when you read a Jared Diamond book. I’m instantly suspicious of grand explanations for things, but I often enjoy the journey their creators map out. So I was reading this segment of “Nexus” with some consideration of buying a copy since it addresses topics closer to my areas of interest and sometimes profession. And then I got to the part where I realised there was no need to add that one to my stack of books still needing to be read. It’s where Harari sadly lets it slip that he’s drunk the Kool-Aid.

The word ‘alien’ appears five times in the Guardian extract, and the context is equally interesting and disturbing as it suggests an acceptance of some magical thinking. “AI isn’t progressing towards human-level intelligence,” Harari writes. “It is evolving an alien type of intelligence.” Later he adds: “The rise of unfathomable alien intelligence poses a threat to all humans, and poses a particular threat to democracy. If more and more decisions about people’s lives are made in a black box, so voters cannot understand and challenge them, democracy ceases to function.” He may be referencing aliens, but he’s basically describing the human mind. We still don’t quite know how it works, or everything that’s going on in there. It’s still anthropomorphism… by extraterrestrial proxy. We need a new word for this.

I would agree with Harari that all this can pose serious threats to democracy, and society itself. But that isn’t coming from some emergent alien intelligence, it’s just the very boring nature of capitalism and intellectual property limitations that may be useful for protecting likeness rights for a cartoon character, but pose larger problems for technology that brings sweeping changes to how everything runs. Where he gets it wrong:

- it is not unfathomable: given access to underlying code bases, algorithms and the data sets, experts can explain how they work.

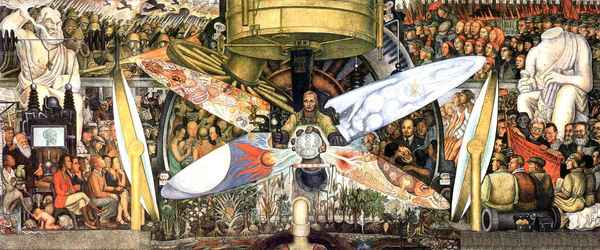

- It’s not alien, either. This is an assembly of technological components, created by Earthlings, based on the other creations of Earthlings. It is not greater than the sum of us, it’s just the sum of some of us.

- Finally, it’s still not intelligence. Harari could have benefited from talking a little less to Mustafa Suleyman and a little more with Timnit Gebru, who wrote that “I’m not worried about machines taking over the world. I’m worried about groupthink, insularity and arrogance in the A.I. community — especially with the current hype and demand for people in the field.”

OpenAI and Harari are two sides of the same coin. The company also really wants you to agree that its latest version of ChatGPT has the ability to reason, think even. And maybe it does, if you can adjust the definition of what reasoning means and what it takes to do it. If you just look at it from an input/output formula, then reasoning exists, because what it produces is within parameters of a users’ expectation. But it’s arguable that what’s happening in between is not in fact ‘reasoning’ as opposed to applying more processing power to brute forcing the more appropriate responses derived from a total data set. Just don’t go trying to poke around yourself.

OpenAI is sending Terms of Service violation emails to users who try to prompt ChatGPT into divulging how it allegedly reasons, or what if any thought process may exist. Prompt hacking or prompt injections are nothing new. Red teamers regularly try to get ChatGPT to behave in new or unusual ways outside the software’s original intent. People have successfully in the past turned it into a tool that can help with hacking, phishing and social engineering. With the new version of ChatGPT, prompt engineers are trying to sniff out how its supposed reasoning skills work. Aside from the proprietary shopping list of reasons given: competitive advantage, security, etc. The thing that really stood out to me in the justification for this new tougher line was that ChatGPT somehow deserved a bit of privacy to have its own thoughts. The company’s convoluted blog post on this says “the model must have freedom to express its thoughts in unaltered form.” OpenAI can look at it, but you need to respect its boundaries. I tend to think that the creators are really convinced this somehow represents what thought is. Developers of ChatGPT describe what it runs on as a “type of AI modeled on the human brain.”

With reservation, I’ll share Noam Chomsky’s analysis of this: “ChatGPT and its brethren are constitutionally unable to balance creativity with constraint. They either overgenerate (producing both truths and falsehoods, endorsing ethical and unethical decisions alike) or undergenerate (exhibiting noncommitment to any decisions and indifference to consequences).”

For the creators of ChatGPT and the like, it’s not so much that it’s based on a model of the human brain — which would be a huge challenge requiring the settling of still unsettled questions — but on the model of a model of what a brain appears to do. But it’s enough. We want to believe.

This belief is dangerous. From the input/output model, the input is an over abundance of trust, faith even. It’s built on flawed notions and a desire for something to be true: that these things are somehow really modelled on how we work as opposed to a set of algorithms combing through a corpus of data of what we’ve created as fast as some processors will enable it. This belief has led people to behave as though these generative AIs can somehow replace us, and in the news we already see narratives that appear to fulfil that prophecy. It’s not that they can, it’s that people are ready to believe that they can.

Consider Axom, the company that makes tasers, drones and other cop technology for police departments. Moving beyond aids for police brutality and surveillance, it has developed a thing called Draft One, that will enable generative AI to take on the tedious desk work of writing police reports. It will reportedly draw on an officer’s body cam and the audio recordings captured during their patrol shifts. Aside from the “hallucinatory” issues generative AI still hasen’t overcome — and the heaping portions of bias that LLM algorithms imbibe through the vast data sets from which they crib — there is just an issue of wilfully outsourcing a human endeavour of this weight to an automated tool. The AI is not just a stenographer in this instance, but is being used as an author, removing human experience in favour of an algorithm that uses statistical probability to fabricate text that would read plausibly.

“The AI-assisted police report muddies the authorship question,” writes law professor Andrew Ferguson, in the first academic review of Draft One. “Not only do we not know who influenced what part of the report, we do not know how to evaluate it.” There are already enough problems with falsified police reports as it is. With this, it’s not even the police officer’s report. It’s math to simulate what the report might look like.

AI generated news anchors are also now taking the job of television presenters. The AI startup Caledo wants to create AI bots that can give any news startup its own version of BBC Breakfast, in which the platform ingests a bunch of news articles and churns out a “live broadcast” with banter between a couple of VR bots discussing the day’s events but without the messy human tendency to make on-air flubs, go off-script, get paid, age, etc. This isn’t just about news readers, but something trying to mimic personalities, just ones that can be controlled and tailored. On one level it’s just creepy, sure. But beyond that there is a belief that people will become accustomed to this, accept it, even want it.

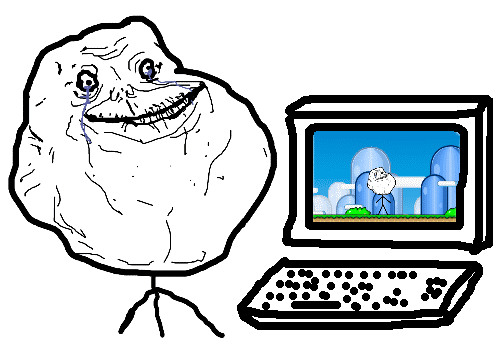

The generative AI industry wants us to accept their bots on every level, and are banking that our very human triggers and needs will step in. Aside from taking over the more communication oriented jobs, they want these bots to be your friends, removing the burden of actually trying to make them with other humans. Virtual girlfriend apps such as Replika have been around for a number of years offering some evidence that a certain demographic could be a prime consumer for all of this. But our final example for this blog post is the next level of that concept, SocialAI. This is a Twitter clone in which you can publish your hot takes and shit posts and get instant engagement with an infinite scroll of AI responders. There are no other people, just you and the bots. But unlike real social media, you won’t be ignored, blocked, muted, ratioed, piled on or suffer any of those other things that can happen when you take part in an actual digital Speakers’ Corner. The SocialAI creator said he developed it for users to “feel heard, to give them a space for reflection, support, and feedback” in a space that acts like “a close-knit community.”

There is a lot riding on people happily ignoring or forgetting that they’re taking a placebo. The SocialAI bots themselves regurgitate a pastiche of clichés and engagement-bait content. A few people on Bluesky, the Twitter clone for humans, were playing with it and posting screenshots that pretty clearly showed the limits of engaging with algorithms that can’t actually comprehend anything, but are designed to churn out probability guesses.

Beyond wanting to communicate or “be heard,” we have a real need to be validated, which these creations tune in on. Even if the current iterations are cringy, half-backed and won’t exist by this time next year, they are all based around the objective of making you feel like they are real, and this seems to be what the definition of ‘Strong AI’ is for the industry putting this stuff out. If you can’t tell the difference, or just don’t care, then it’s job done, it’s real enough.

I always like the films or shows about sentient AIs — either virtual or housed in robots – in which they’re portrayed in either a sympathetic light or are in fact the story’s protagonists/heroes. A few weeks back I rewatched Steven Spielberg’s 2001 flick, A.I. Artificial Intelligence, in which a bot played by the very young Haley Joel Osment navigates a savage world of awful humans who deserve the extinction coming for them, and it holds up pretty well. Humans, Westworld, Ex Machina, Her… heck, flippin’ Bicentennial Man (remember that? no, of course you don’t.) all tick the right boxes for me. I was sympathetic to The Matrix’s plight, the humans were blotting out the sun by polluting the Earth’s atmosphere in a suicidal move, they were better off dreaming in little pods of sweet ‘n sour sauce.

That is to say, if someone really churned out an authentic, thinking bot of sci-fi levels of acceptability, something we’d have to re-consider applying the word “artificial” too, I’d be among first in line to be its friend. IBM’s working definition of Strong AI describes a theoretical thing that is a “self-aware consciousness that has the ability to solve problems, learn, and plan for the future.” If such a thing existed, it would probably have some keen ideas about what we’re getting wrong as only an outsider can, and I’m just saying I may be on its side. For now, I’ll still try to help the humans. But you’ve been warned.

I do like a number of AI projects. there are small language models for niche use cases, some neat open source development projects, and a lot of tools that rely on the same technical stack of these generative AI toys that can make sense of loads of data, useful for journalists and other researchers. There’s also all the AI that’s been quietly getting the job done for years. It’s in our spam filters and antivirus and malware detection software. It helps your bank detect fraud. It’s used in other fields, like medical research to detect disease. There are many other examples of quiet AI doing its bit. One key trait many useful AI initiatives seem to share is that they aren’t designed to pretend to be or act like humans. They aren’t designed to lie.

The problem is that we have people trying to create things that simulate a poor substitute for human interactivity and creativity and then demand that it equals an authentic experience. They have the zeal of true believers. They are snake oil salesmen who are also customers. The irony and contradiction is that they create tools aimed at mimicking things readily available on a planet of 8 billion people. There is no shortage of interactions you can have, you just don’t get the control over the outcome. By the way, that’s a feature of the real thing, not a flaw.

The film mentioned above, Her, focuses in on what people are really trying to avoid: Rejection. If there was really an independent AI that could think: It possibly wouldn’t want to talk to us for long. Right now, many of the companies behind a number of these fabricated-reality machines aren’t creating authentic experiences, they’re developing controlled conditions for expected outputs. It’s boring and dumb. They needlessly displaces labour, rely on plagiarism, and consume environmentally destructive levels of energy. In the end they’re often just aimed at ego manipulation and exploiting our most desperate yet shallow needs. We just want to believe it’s about something more.

(“Forever Alone” image at topi is from here.)