In praise of bubbles

Platforms are called 'social networks' for a reason. They're aimed at facilitating social exchanges. You build social circles on them. Round things, like bubbles.

Remember Google+ ? Of course you don't. Internet memories are short. It's been in the Google Graveyard now for a few years along with many other good, bad and ugly experiments the company that is now Alphabet has toyed with. Google is proof that online you owe no one anything. People loved Google Reader, didn't matter. BANG! dead. Not many people loved Google+, and you can understand why. It was a mess, trying to integrate into various Google services in ways that didn't make sense, making it harder for people to understand which information on their accounts was more public than they intended. People who didn't realise they had accounts discovered they did.. The minimalist, high-contrast Kennedy approach to unified aesthetics and UI aside, it was also... and data breachy. This isn't to unpack any of that old luggage, but to look at one thing G+ got right: Circles!

Circles made sense. You'd generate a little chart that looked like an old rotary phone dial and then add your contacts to it. You could have one called "work colleagues I want to have a drink with" and another for "all work colleagues," allowing you to arrange after-work drinks that don't include Chet. You could have a group for your hometown that includes all your family and friends, so they know when you're visiting, and another without your family for the real planning. In reality, it was like creating little Venn diagrams of what you're more likely to say to whom, depending on the context. There are people with whom you only want to only talk about. And then there are people you never want to talk to or hear from. There are other ways of achieving this, but the user interface made it easy. All bubbles eventually pop, and new ones form elsewhere simultaneously.

Fast forward to Bluesky...

- In 2019, Twitter Jack announced a plan to develop "a decentralized social media standard," even though ActivityPub was right there. It was going to be the ultimate "free speech" thing ("Man plans; God laughs." — Yiddish proverb). Time passed. While Jack was tinkering with his new hobby, Brother Elon embarked on a diva-level "will he/won't he" acquisition of Twitter that was basically the wildest public display of "what the fuck?" the business world had ever seen. He ended up walking into Twitter HQ in 2022 with a kitchen sink in an obscure reference to something that was lost on everyone. I understand this. I also often laugh at my own jokes while no one else gets them. They don't cost several hundred million dollars, though.

- In 2023, Bluesky began its invite-only beta phase, attracting adults with "cool kids" complexes who need to be first. eBay suddenly became rife with scalped invite codes. It was fun and strange in those days. It broke a lot. There was a disconcerting amount of lewds on main, mixed with a lot of dad jokes and then occasional sprees of NSFW memes about Alf. Users created their own language for things. For example, 'skeeting' referred to posting something, and it was popularized before many people looked up the word's meaning. That year, Elon changed Twitter's name to 𝕏, a Unicode character from a mathematical alphabet subset used to represent an unspecified variable. He eviscerated the Trust and Safety team, closed down open access to the API, and pretended to open-source its algorithm but really didn't. He made a weird, identity-politics based pricing structure: The platform would validate you as anyone you wanted to be for just a few quid. More crypto bros, bots, and scam accounts joined. Jack changed his mind: his old site was now the free speech platform. His new Bluesky thing was, in his mind, making the same mistakes Twitter did when he owned it. Jack doesn't seem to like how he runs his own platforms.

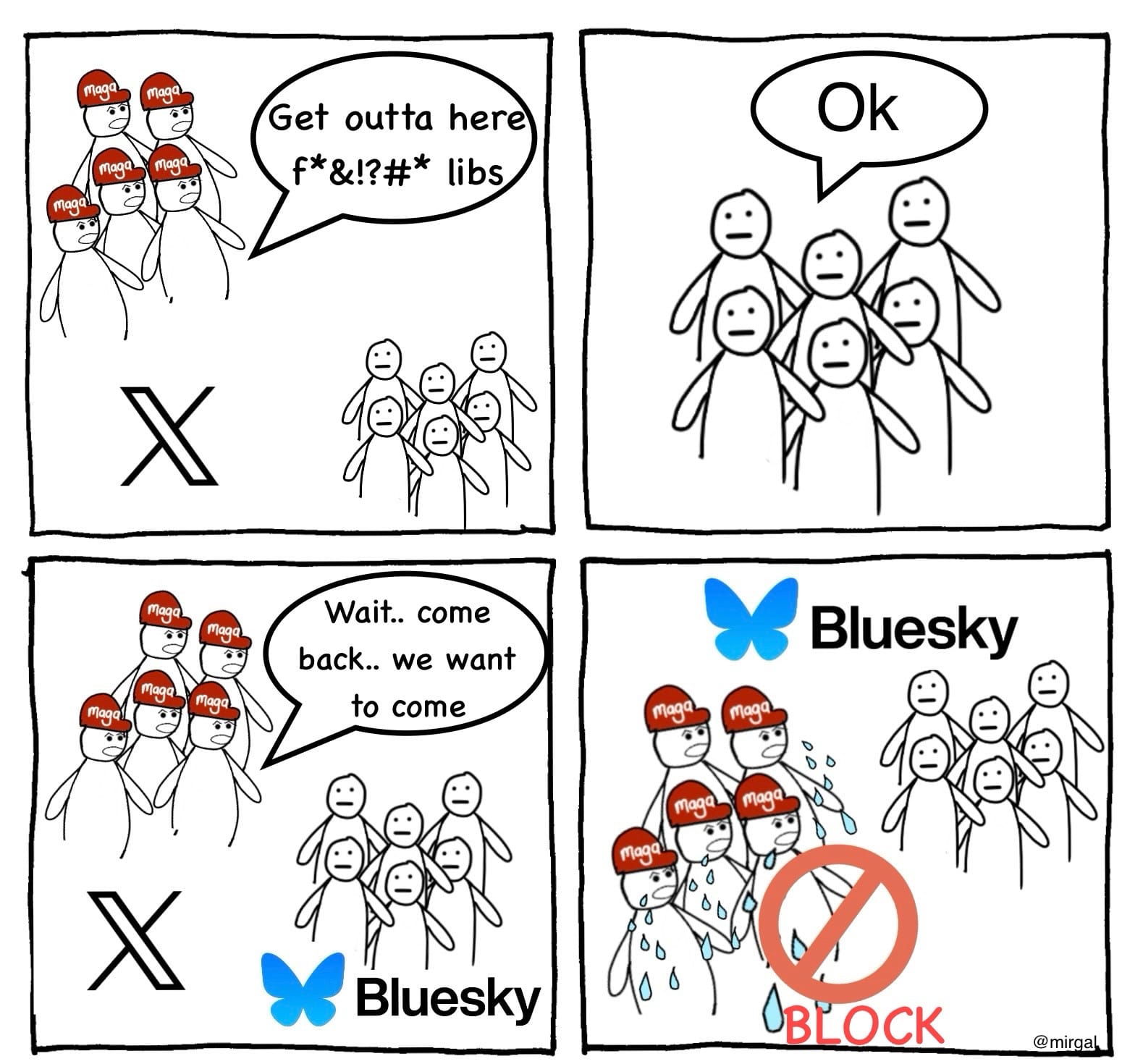

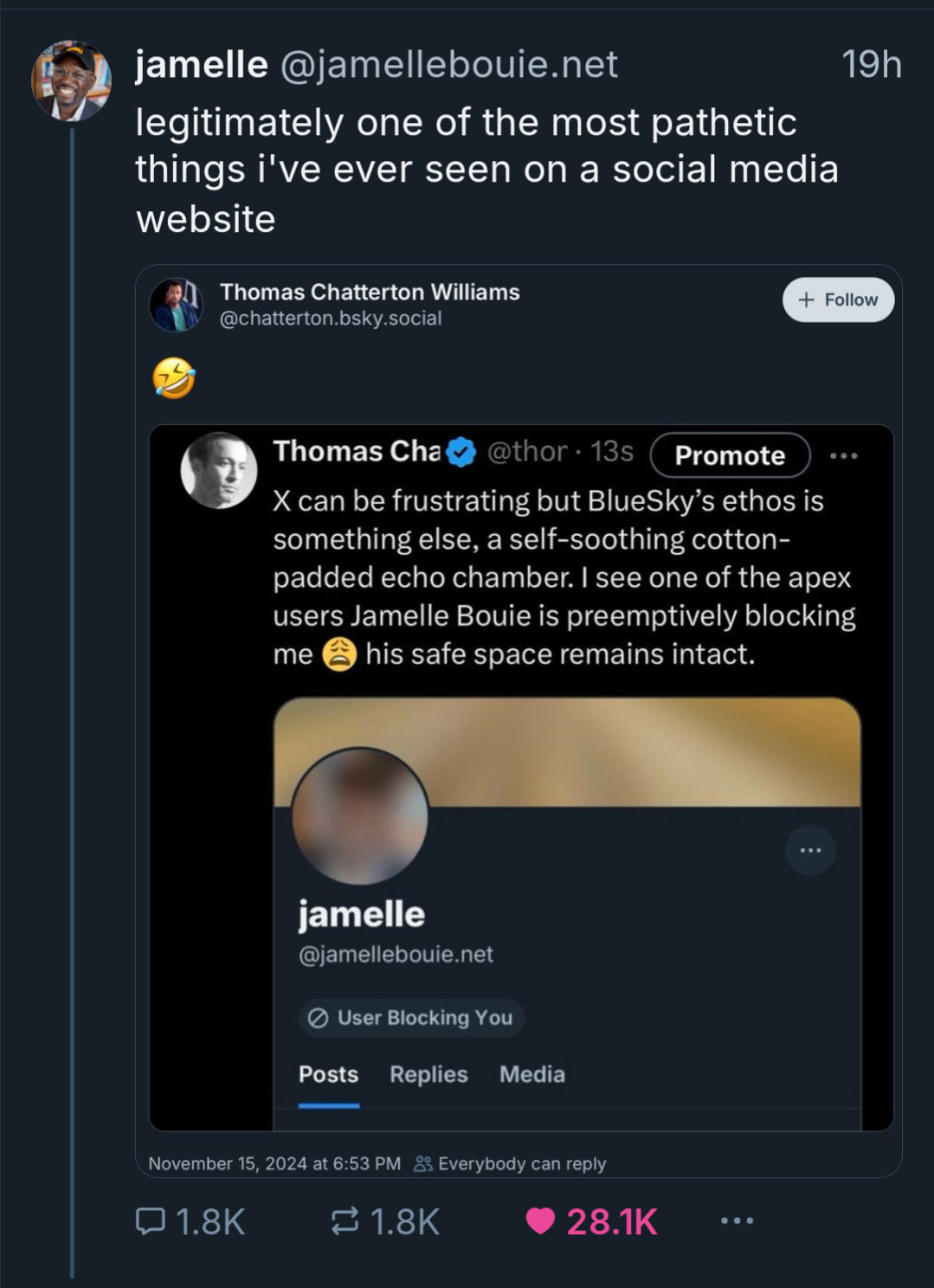

- In 2024, Bluesky opened to just anyone. It's user base jumped into the millions over the next few months. Jack left its board to spend more time with the neo-Nazis, strange libertarians, and crypto scammers on his other 'free speech' platform, Nostr. Elon paid for Trump to win the presidential election. Elon's mum was proud of him. Multitudes of his site's users sought refuge from the trash fire that was once Twitter — now resembling a second Truth.Social — and migrated to Bluesky, which hovered around 20 million users. And now, in late November, Bluesky users have started reporting sights of a higher influx of MAGAs and other "just asking questions" types lurking around as well. Reasonable people who had been driven away by these users on 𝕏 blocked them, as you'd expect.

Bubbles are normal

Bubbles get a bad rap. They're blamed for fermenting misinformation, spreading disinformation, and being petri dishes for extremist circle jerks... among other things. All of that stuff happens, of course. They also happen in meetings, at people's houses, or when any group of friends go out somewhere and hang out with one another. That's because bubbles are how people socialise. A social network platform is for socialising. The idea that you change humans by enforcing how they choose to socialise doesn't work, unless the point is to just start fights.

Consider this: Most people go to the pub to meet friends, chat, commiserate, gossip, complain about sports, current events, rent, or have a laugh. Inevitably a couple of louts will show up for a fight. They are thrown out. That's not called a bubble, it's just seen as good maintenance of the space.

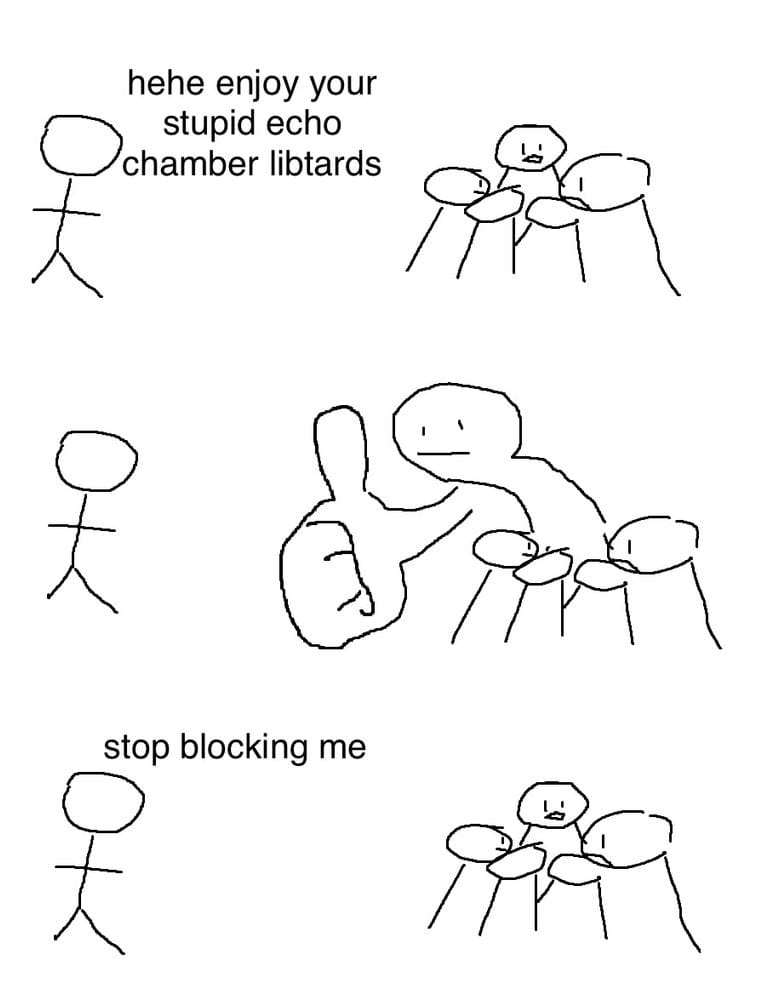

"The accusation these weirdos fling at sites like BlueSky is that it’s an echo chamber, a bubble of ignorance made by poor sensitive souls who don’t want to hear other opinions or engage in the marketplace of ideas. It’s the pseudo-intellectual version of that one guy in your mentions who won’t stop asking you to debate him." — Kayleigh Donaldson

Right wing trolls, 'phobes and other varieties of hatey people enjoyed it when Elon deleted tools some folks used on Twitter to self-moderate who they interacted with. The horde got that dopamine hit of entitlement as their favourite punching bags were suddenly available. As a result, a lot of people with more liberal and/or left leanings, or who are just highly targeted by hateful shitwads, moved on. Some went to Mastodon and other platforms, but quite a lot moved on to Bluesky.

Finally, having chased off the people they seem to despise, a number these users must have been left with nothing to do. So, they followed. A pithy observation: It seems to me a lot of left-leaning, progressive folks and liberals enjoy one another's company. There are huge disagreements and flame wars, but generally they tend to look for spaces to be around one another to compare notes. When far right agitators drive them off a platform, they don't then just hang out with each other on that place, they want to move on to the next place that the people they claim they oppose have moved to. They can't quit us. But really, they're just looking for the next fight.

The echo chamber has its use cases

"Echo chambers are not the enemy. They’re places where people find community, affirmation, and, most importantly, peace. The critics act like Bluesky users are huddling in bunkers whispering forbidden truths. In reality, they’re trading recipes, sharing obscure band recommendations, and occasionally discussing how many chickens it would take to defeat a bear (the current consensus is 73)."

— M - Zola on their Rejoin Dossier Substack

In the Financial Times, Bluesky is "a silo." Jemima Kelly writes in a bizarrely (for FT) un-paywalled opinion piece that "I’m not sure I have ever felt more like I’m at a Stoke Newington drinks party than when I’m browsing Bluesky (including when tucking into Perelló olives and truffle-flavoured Torres crisps in actual N16)." Sounds nice! Kelly makes good points in the piece; this isn't a dig. She brings up the problematic notion of the "town square" approach to platforms, in which different political sides allegedly engage with one another, while messy, she writes, it is preferable to the "echo chambers." The problem with this is what people think a town square is.

We have a town square online. It's the web. On it, people can make anything and attract all sorts to it. When you go online (assuming you're able to access a relatively uncensored internet where you live) you're in the town square. There's a shop, here's a chemist. There's a Starbucks, here's the funky little indie coffee shop (choose that one). Over there is a guy standing on a step stool ranting about the 5G networks reading his mind, give him a wide berth. Most of us are not a member of just one platform or all of them. And on any of the platforms we do choose, we're curating the experience. That's also what you do when you go to town. People on Bluesky know what their political or social opposites are saying about them. They're sharing screenshots of it and trading snarky remarks about it. This is how normal people behave in daily life. You pass by the preacher with the megaphone at the tube station entrance shouting about how we're all doomed to go to hell. You are aware of his message and his general thoughts about you without engaging him with... the discourse.

In The Atlantic, Ian Bogost laments that Bluesky and micro blogging platforms like it represent a bubble of a slightly different type: a step backwards to an earlier kind of social platform, but without the user base. You can't complain to Sky Broadband on Bluesky when the fibre craps out. This was actually something I kind of miss about old Twitter, but in a lot of ways, the weird older web when corporate giants weren't quite there on the engagement platforms was quite nice, too. The biggest echo chamber online today is that all the things can be commodified. (Aside: I just like it when I open each Atlantic article in a containered anonymised browser session with no user history and it tells me "This is your last free article.")

The echo chamber we curate for ourselves is also — particularly in increasingly fraught times in national and global politics — where we can hear that we aren't alone. Spending time with your community doesn't mean you're opting out of the rest of the world, it's often how you endure it. It's where you relax or recharge, bounce ideas off of people you trust, like or at least respect. Maybe you get inspired by someone else's ideas who's coming from a similar place. And this is the real threat that conservative forces see because they do have places like this of their own. The web is full of right wing hate forums, chat rooms and Facebook pages. Unless your job is actively monitoring these, there is no mental wellbeing upside to lurking in them. Barnstorming them with your own truth bombs is not going to fix anything. This isn't to make a false equivalence: Your echo chamber — without the racism, gender violence references and migrant bashing — is not as bad as theirs.

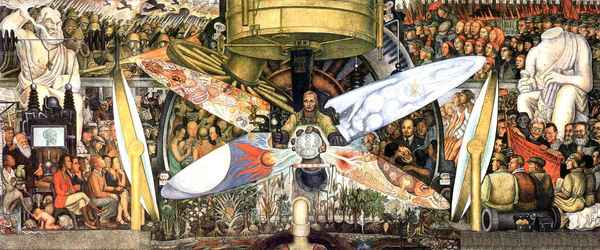

Blocklists, muting etc. is what we have because so much of what the large platforms did have failed us all. The original echo chambers on social media were supplied by opaque algorithms that were designed to appeal to advertisers trying to sell you sneakers but over time leveraged by interest groups, lobbyists and political campaigns to micro-target users with tailored messaging to hate or fear this group or that one, or surface more and more content that will generally conform to whatever the machine learning thinks you'll click. It was the lazy person's echo chamber. They weren't forced to hand-craft bespoke artisanal echo chambers like I had to in the '90s across myriad funky little forums made on clunky forums or online chat groups. The new wave of federated social sites is a step backwards, in some very good ways.

Tiny bubbles

I don't want to see the end of bubbles, but rather more of them popping up, all over in different shapes and sizes. The federated, decentralised platforms don't have algorithms baked into them to surface everything for you. You've got to dig. It used to be something we knew how to do. You pick where you're going to rock up to, who you talk to, what you want to see and — vitally — what you exclude. You don't let some automation endlessly exploiting your data to make educated guesses. Real town square shit.

Bluesky is an ostensibly unfinished project, it's one reason I relate to it. There are some good blocking tools and self-moderating efforts like block lists that somewhat make up for that. But no real organised, serious moderation investment and it shows. The difference has been the user base that is doing the lifting with one another by taking advantage of an open API and shareable blocking and muting lists. I follow one called "MAGA/reactionary troll accounts" that's curated by an author on the platform who I think does a good job at picking the right accounts for it. Clearsky, when it's working, show's I'm blocking a few hundred accounts. I'm also blocked by something like 217 users, no idea why, not bothered. I'm on one block list called "Biden haters" or something like that, which I'm fine with.

When you hang out with a group of people at the park, in town or nearly anywhere, it's true that you're out in public, but you're also curating that experience and prioritising who you're paying attention to. Being on a social platform is basically that. Unless the site is called "fight me" you don't owe people who despise you any time. Bubbles are ephemeral things, especially on the internet. But they have their uses. Maintain yours.